|

| Click for a larger image |

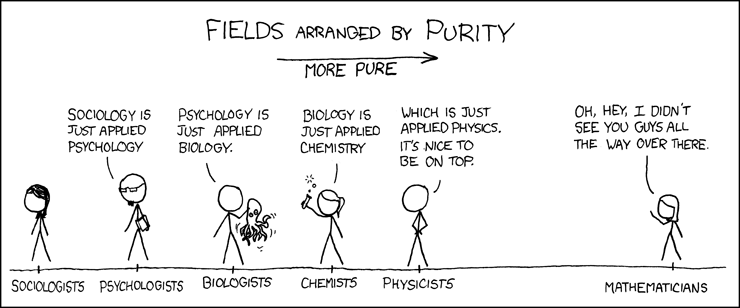

Essentially, the reaction is that, as a social science, psychology isn't a "real" science like biology, chemistry, or physics. I encounter this reaction often enough, even among otherwise scientifically savvy people, that I am often tempted to do silly things like shout, punch things, or at the very least launch into an ill-advised rant.

Fortunately, I do none of these things. As I have discussed previously, the reaction that social sciences are pseudoscientific is rooted partly in the knee-jerk intuition that understanding people is easier than understanding "hard science" topics like physics and chemistry, and therefore that social scientific truths are less valuable than truths discovered in other sciences. Therefore, I consider it part of my duty as a social scientist to be a force of enlightenment, and consequently grit my teeth and explain as gracefully as possible that the defining features of science are rooted in method rather than content. Science is defined by an interplay between evidence and theory, not the particulars of the content studied.

Deep in my heart, though, I know that these reactions are rooted not only in human biases, but also in the very slow, non-cumulative character of the advance of the social sciences. The "harder" sciences are responsible for large numbers of inventions and increases in human comfort. The social sciences do not have as impressive a track record. For another source of evidence, consider the following figure, taken from a paper in PLoS One by Daniele Fanelli:

| Figure 1 from Fanelli (2010) |

The above figure shows, across a variety of disciplines, the proportion of papers claiming to have found support for the authors' predictions. Science being what it is, we should expect that regardless of the discipline, sometimes scientists get it wrong -- the results of their experiments do not support their original predictions. Disciplines that have a low proportion of papers reporting these sorts of experiments either have theories so powerful as to make experimental predictions a trivial exercise, or, perhaps more likely, have theories so flexible and imprecise that they are nigh infalsifiable. And, of course, the discipline with the highest proportion of papers claiming to support the original experimental predictions is psychology.

Consider a second figure, this one taken from John Ioannidis' provocatively named paper, "Why most published research findings are false":

Ioannidis constructed a variety of models designed to show the probability that a research finding is true (what he calls the "positive predictive value", or PPV) under various research conditions. Through his model, Ioannidis identified three factors that decrease the probability that a research finding is true:

1. An inadequate number of observations (for those familiar with statistics, inadequate statistical power, which Ionnidis labels 1 - β). Fewer observations decrease the chances of detecting true relationships that actually exist in a given study, and thus decrease your confidence that the reported relationships in a study are actually true.

2. A large number of tested relationships. As the number of tested relationships goes up, the ratio of true to false relationships in the study (which Ioannidis labels R) typically goes down. Thus, your confidence in a study's reported relationships should also go down.

3. Factors, such as financial incentives, researcher ideology, flexible research designs, that increase researcher bias (which Ioannidis labels u). The presence of these factors straightforwardly decrease your confidence in a study's reported relationships.

Unfortunately, low power, a large number of tested relationships, and researcher bias are all characteristics that typify social science research. By my own (admittedly speculative) estimation, row 6 in Ioannidis' Table 4 best represents the typical psychology experiment: low power, a large number of tested relationships, and a moderate amount of researcher bias due to either a flexible research design and / or a researcher attempting to support his or her "pet theory". Ioannidis gives the results of that study a .12 probability of being true.

Given the above evidence, is the quest for social scientific truth entirely quixotic? Not necessarily. Social science (psychology among them) is a difficult enterprise. Difficulty, though, is not the same as impossibility. In the face of difficulty, it is absolutely incumbent on social scientists to conduct their research in ways that increase confidence in their findings. Ioannidis pointed out some of these factors -- large numbers of observations, a focus on a few variables, and strong research designs that are independent of researcher ideology and financial interests. As more social scientists design their studies in these ways, perhaps we can hold out hope that the social sciences will develop more of the cumulative character of the harder sciences.

References:

Fanelli, D. (2010). “Positive” results increase down the hierarchy of the sciences. PLoS ONE 5(4): e10068. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010068.

Ioannidis, J. (2005). Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Med 2(8): e124. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124.

I would add to this discussion that our philosophy of science is rather antiquated and immature. We have, essentially, a Machian positivistism and operational definitionalism that was discredited long ago, but remains the primary methodological locus of psychological research. It's unfortunate, because Donald Campbell's evolutionary epistemology (or some version of it) is, in my opinion, a much better way of thinking about science, and he was a social scientist. Experiments should be primarily for discovering constraints on theory, selecting out hypotheses, and selecting out theories when hypotheses (or a significant number of hypotheses) fail critical tests against other theories. Instead, most of what we do is select in (by failing to rule out, statistically) hypotheses, and by extension, theories. Furthermore, we reject any other selection criteria as being "armchair philosophizing". In -principle arguments, for instance--logical incoherence, circularity, infinite regress, etc. We had a brownbag in my department discussing the Bem "precognition" paper; one person asked why the physicists don't feel worried by this data, as it seems to contradict basic principles in physics. The reason, I would imagine, is that they have more sophisticated selection criteria than significant differences.

ReplyDeleteExcellent insights.

ReplyDelete